In the world of construction, the humble block wall stands as a ubiquitous element, forming the backbones of buildings, retaining earth, and defining boundaries. Yet, its true strength lies not in the blocks themselves, but in the unseen network of steel reinforcement coursing through its veins.

This article delves into the critical role of vertical rebar in block walls, exploring not just the common knowledge found across the internet, but also a deeper, more fundamental understanding of the materials and principles at play. We will journey from the atomic structure of steel to the complex chemical reactions within the grout, providing a level of detail that demystifies this essential construction practice.

The Fundamental Purpose of Vertical Rebar: Beyond Simple Support

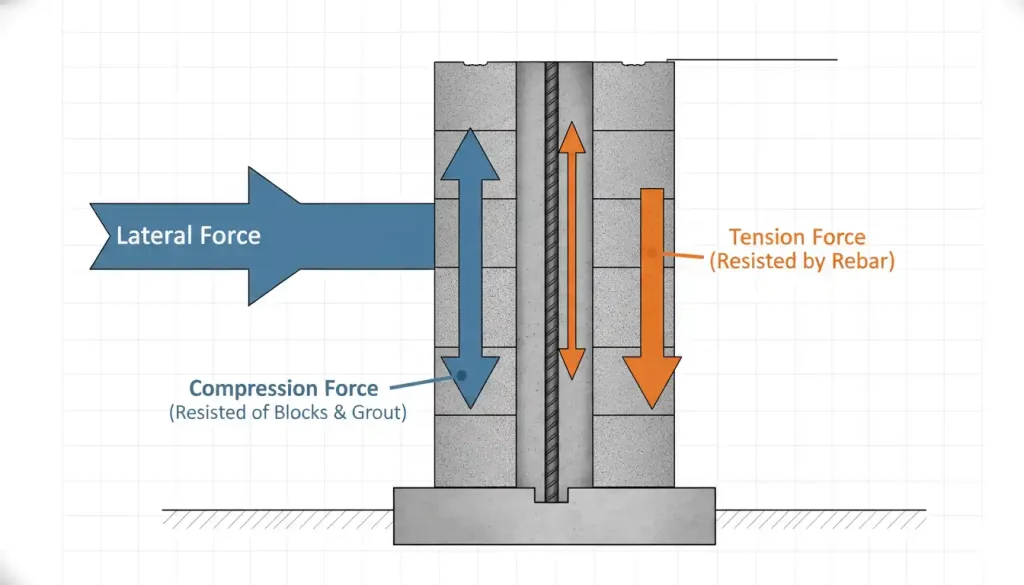

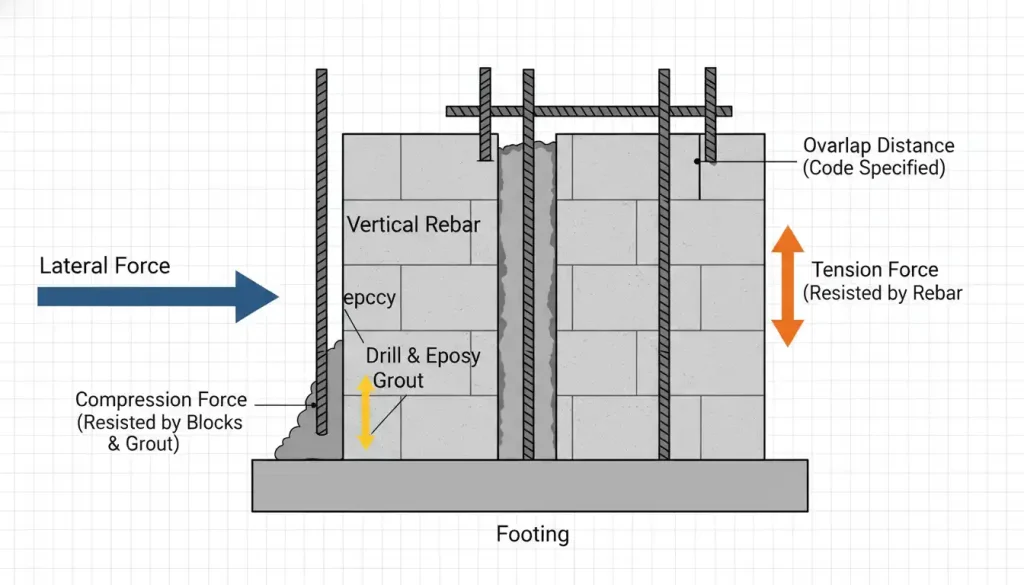

At its core, the function of vertical rebar in a block wall is to counteract forces that the blocks themselves are ill-equipped to handle. Concrete blocks, like concrete in general, possess immense compressive strength, meaning they can withstand significant pushing forces. However, they have very poor tensile strength, making them vulnerable to pulling or bending forces. These tensile forces can arise from various sources, including wind loads, seismic activity, and the lateral pressure of soil against a retaining wall.

Vertical rebar, embedded within the hollow cores of the blocks and surrounded by grout, creates a composite material that marries the compressive strength of the block with the tensile strength of the steel. This synergy is what gives a reinforced block wall its resilience. When a lateral force pushes against the wall, one side is put into compression while the opposite side is put into tension. The concrete blocks and grout easily resist the compression, while the vertical rebar on the tension side engages to prevent the wall from cracking and failing. For more information on the basics of reinforced concrete, you can visit the Concrete Network.

The Molecular Dance of Strength

What is truly happening at a microscopic level is a fascinating interplay of materials. Steel, the primary component of rebar, is a crystalline lattice of iron atoms with a small amount of carbon. This carbon content is crucial; it introduces imperfections in the iron’s crystal structure, which prevents layers of atoms from sliding past each other easily. This resistance to slippage is what gives steel its high tensile strength. When a tensile force is applied to the rebar, the energy is distributed throughout this strong, interlocking crystal structure.

The concrete block and grout, on the other hand, are a complex matrix of cement paste and aggregates (sand and gravel). The cement paste is composed of calcium silicates that, when mixed with water, undergo a chemical reaction called hydration. This reaction forms a dense, interlocking network of calcium silicate hydrate crystals that bind the aggregates together. This crystalline structure is excellent at resisting compression, as the atoms are already tightly packed.

The bond between the rebar and the surrounding grout is not merely mechanical, relying on the rebar’s deformations (ribs) to grip the grout. There is also a chemical bond that forms at the interface, further enhancing the transfer of stress from the concrete to the steel.

The Thermal Tango

A critical, yet often overlooked, aspect of the rebar-concrete partnership is their nearly identical coefficients of thermal expansion. Both steel and concrete expand and contract at very similar rates in response to temperature changes. This compatibility is a fundamental reason for the success of reinforced concrete.

If their expansion and contraction rates were significantly different, temperature fluctuations would cause internal stresses at the rebar-grout interface, leading to microscopic cracks that could eventually compromise the wall’s integrity. This “thermal tango” ensures that the two materials move in harmony, maintaining their bond and structural integrity over a wide range of environmental conditions.

Types of Vertical Rebar: A Matter of Material Science

The most common type of rebar is carbon steel, often referred to as “black bar.” However, different environments and structural demands necessitate a variety of rebar types, each with unique properties rooted in their composition and manufacturing.

- Carbon Steel Rebar: The workhorse of the construction industry, it is cost-effective and provides excellent tensile strength. Its primary drawback is its susceptibility to corrosion (rusting) when exposed to moisture and chlorides.

- Epoxy-Coated Rebar: To combat corrosion, carbon steel rebar can be coated with a layer of epoxy. This coating acts as a barrier, protecting the steel from corrosive elements. However, the coating can be damaged during handling and installation, compromising its effectiveness.

- Galvanized Rebar: This type of rebar is coated with a layer of zinc. The zinc provides a sacrificial protective layer; it will corrode in preference to the steel, a process known as cathodic protection.

- Stainless Steel Rebar: Offering the highest level of corrosion resistance, stainless steel rebar is also the most expensive option. It contains a minimum of 10.5% chromium, which forms a passive, self-healing oxide layer on the surface that prevents rust.

- Glass-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (GFRP) Rebar: A composite material made of glass fibers set in a polymer resin, GFRP rebar is lightweight, corrosion-proof, and non-conductive. However, it has a lower modulus of elasticity than steel, meaning it will stretch more under the same load. More details on GFRP rebar can be found at CompositesWorld.

The Atomic Shield Against Corrosion

Corrosion is an electrochemical process. In the case of carbon steel rebar, iron atoms lose electrons and become ions, essentially dissolving into the surrounding moisture. The presence of chlorides, from sources like de-icing salts or marine environments, accelerates this process dramatically.

The chromium in stainless steel is the key to its “stainlessness.” Chromium has a very high affinity for oxygen. When exposed to the air, it instantly forms a thin, transparent, and incredibly stable layer of chromium oxide on the surface of the steel.

This passive layer is inert and non-reactive, effectively acting as an atomic shield that prevents oxygen and moisture from reaching the iron atoms, thus halting the corrosion process. If this layer is scratched, the exposed chromium will immediately react with oxygen in the air to reform the protective layer.

The Menace of Microbial Corrosion

While chemical corrosion is a well-understood phenomenon, a lesser-known threat to the longevity of steel reinforcement is microbially induced corrosion (MIC). Certain types of bacteria can thrive in the anaerobic (low-oxygen) conditions that can exist within a grouted block wall.

These microorganisms can produce acidic byproducts that can aggressively attack and degrade steel rebar, leading to a loss of structural integrity over time. This is a particularly relevant concern in environments with high organic content or potential for water infiltration.

The specification of corrosion-resistant rebar types, such as stainless steel or GFRP, can be a proactive measure against this insidious form of deterioration.

Installation of Vertical Rebar: Precision from the Ground Up

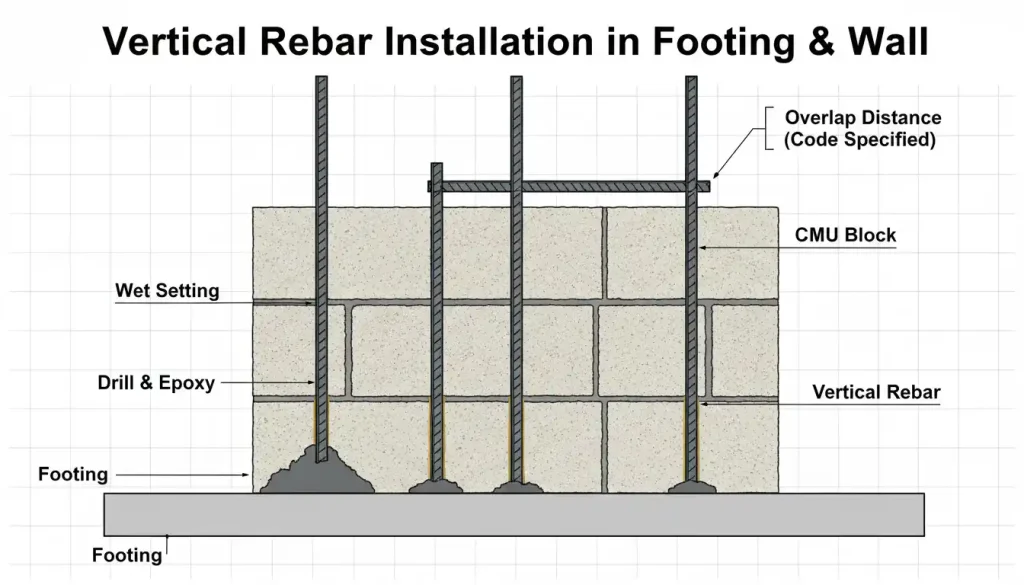

The proper installation of vertical rebar is paramount to the strength of a block wall. The process begins with the footing, the concrete base upon which the wall is built.

Setting the Rebar in the Footing:

There are two primary methods for securing the vertical rebar in the footing:

- Wet Setting: The rebar is pushed into the fresh, wet concrete of the footing immediately after it is poured. While this method is quick, it can be difficult to achieve precise placement and ensure the rebar remains plumb.

- Drilling and Epoxying: After the footing has cured, holes are drilled into the concrete at the specified locations. A high-strength epoxy adhesive is then used to anchor the rebar in the holes. This method allows for much greater accuracy in rebar placement.

Once the starter bars are in place in the footing, the concrete blocks are laid in courses. The vertical rebar extends upwards through the hollow cells of the blocks. If the wall is tall, additional lengths of rebar are lapped with the starter bars, with the overlap distance determined by building codes to ensure a continuous transfer of tensile forces.

Spacing of Vertical Rebar:

The spacing of vertical rebar is not arbitrary; it is dictated by engineering principles and local building codes. Common spacing is typically 16, 24, 32, or 48 inches on center, depending on the height of the wall, the anticipated loads, and the seismic requirements of the region.

Rebar should also be placed at corners, on both sides of openings (like doors and windows), and at the ends of walls.

The Physics of Load Path

The spacing of the vertical rebar is a direct application of load path principles in structural engineering. The goal is to create a continuous and efficient path for tensile forces to travel from the top of the wall, down through the rebar, and into the foundation.

When a lateral force is applied, the rebar acts like a series of vertical beams, transferring the load downwards. If the spacing is too wide, the sections of unreinforced block between the rebar can become stress points and potential failure zones.

The closer spacing in high-load or seismic areas ensures that these forces are distributed more evenly among a greater number of reinforcing elements, reducing the stress on any single point.

The Grout Key and Mechanical Interlock

When grout is poured into the cells containing rebar, it doesn’t just surround the steel. The grout flows into the small crevices and imperfections of the inner surfaces of the concrete blocks. As the grout hardens, it creates a “grout key” – a mechanical interlock between the grout column and the block.

This interlock is crucial for transferring the lateral loads from the face of the block, through the grout, and finally to the vertical rebar. A poorly consolidated grout column with voids can significantly weaken this load transfer mechanism, even if the rebar itself is correctly placed.

Grouting: The Final Step to a Monolithic Structure

Grouting is the process of filling the hollow cores of the block wall that contain rebar with a fluid mixture of cement, sand, and water. This is a critical step that transforms the individual components—blocks, rebar, and mortar—into a solid, monolithic structure. The grout serves several vital functions:

- Bonds the Rebar: The grout creates a strong bond with the vertical rebar, allowing for the transfer of tensile stresses.

- Unifies the Wall: It locks the individual blocks together, enabling them to act as a single structural unit.

- Protects the Rebar: The alkaline environment of the cured grout provides a passive layer of protection against corrosion for the steel rebar.

Grouting is typically done in “lifts,” or sections of wall height, to ensure the pressure of the wet grout does not blow out the mortar joints of the lower courses.

For taller walls, clean-out holes may be left at the bottom of the first course to allow for the removal of any mortar droppings before grouting. The Quikrete website provides information on commercially available grout products.

The Chemistry of a Solid Fill

Grout is not simply watered-down mortar. Its formulation is specifically designed for flowability to ensure it can completely fill the voids in the block cells without segregation of its components. The hydration reaction of the cement in the grout is an exothermic process, meaning it releases heat.

This heat of hydration is an important consideration, especially in large grouting pours, as excessive heat can lead to thermal cracking. Admixtures are often added to grout to control its properties, such as plasticizers to improve flowability or retarders to slow down the setting time in hot weather. The water-to-cement ratio is also critical; too much water will result in a weaker, more porous grout that is less effective at protecting the rebar and transferring loads.

The Vibrational Consolidation and the Enemy Within

To ensure a solid, void-free grout column, the grout is often consolidated using a mechanical vibrator. This process uses high-frequency vibrations to agitate the wet grout, causing it to flow more easily and release any trapped air bubbles.

What is not often discussed is the potential for over-vibration. Excessive vibration can cause the components of the grout to segregate, with the heavier aggregates sinking to the bottom and the lighter cement paste and water rising to the top. This can result in a non-uniform and weakened grout column.

Furthermore, a significant “enemy within” a block wall is the mortar that can fall into the cells during the block laying process. These “mortar fins” can create blockages that prevent the free flow of grout, leading to hidden voids within the wall that can trap moisture and compromise the bond with the rebar. This is why the use of clean-outs and careful construction practices are so essential.

Building It Right in Your Area: Local Codes and Environmental Factors

While the principles of reinforcing block walls are universal, their specific application can vary significantly depending on your geographical location. Local building codes are the ultimate authority on construction requirements, and they are tailored to address the unique environmental challenges of a region. For residents in the area, it is crucial to consult with the local building department to ensure your project complies with all current regulations.

For example, coastal areas may have more stringent requirements for corrosion protection due to the salt-laden air. This might necessitate the use of epoxy-coated, galvanized, or even stainless steel rebar. Inland areas with expansive clay soils may require more robust foundations and reinforcement to resist soil movement.

In regions with high seismic activity, the size and spacing of vertical rebar are of paramount importance. Building codes in these areas will specify larger diameter rebar placed closer together to withstand the intense lateral forces of an earthquake. The detailing of the connections between the wall, the footing, and the roof structure will also be much more rigorous.

Understanding the specific requirements for your location is not just about passing an inspection; it’s about ensuring the long-term safety and durability of your structure. Always work with qualified local engineers and contractors who are familiar with the nuances of your region’s building codes and environmental conditions.

By understanding the intricate science and engineering principles that govern the use of vertical rebar in block walls, we can appreciate that this seemingly simple construction element is, in fact, the linchpin of a sophisticated and resilient structural system. It is a testament to the power of combining materials to create a whole that is far greater than the sum of its parts.