In the world of tile installation, few product combinations are as ubiquitous as thinset mortar and a liquid-applied waterproofing membrane like RedGard. This pairing forms the backbone of countless durable and water-tight showers, bathroom floors, and wet environments.

However, the seemingly simple choice between “modified” and “unmodified” thinset over this iconic red membrane is a topic rife with conflicting advice, subtle nuances, and significant long-term consequences if misunderstood.

We will move beyond surface-level recommendations to provide a comprehensive, expert-level understanding of this critical relationship. We will delve into the underlying science of how these materials interact, present advanced techniques gleaned from professional practice, and uncover deeply overlooked realities that most installation guides fail to address.

The goal is to equip you not just with the “what,” but the “why,” enabling truly professional, long-lasting results.

Chapter 1: Understanding the Core Components: RedGard and Thinset Mortars

The Common Knowledge Base

At its core, the practice is straightforward. An installer first applies RedGard, a liquid elastomeric waterproofing material, to a suitable substrate like cement backerboard. This creates a continuous, monolithic waterproof barrier. Once the RedGard has fully cured—transitioning from its wet pink color to a solid, dark red—tile installation can begin using thinset mortar as the adhesive.

The primary decision at this stage is selecting the type of thinset. The two main categories are:

- Unmodified Thinset: A basic mixture of Portland cement, sand, and water-retention agents. It is also known as “dry-set mortar” and cures through a chemical reaction with water called hydration.

- Modified Thinset: This type starts with the same base ingredients as unmodified thinset but includes added latex/polymer additives. These polymers, which can be introduced in either liquid or dry form, enhance the mortar’s performance by increasing its bond strength, flexibility, and water resistance.

The common guidance often hinges on the manufacturer’s recommendation. Custom Building Products, the manufacturer of RedGard, generally recommends a high-quality modified thinset for use over their membrane. This is a key point of divergence from other systems, such as Schluter-Kerdi membranes, which famously require unmodified thinset.

The Chemical and Physical Interactions at Play

To truly grasp why one type of thinset is preferred over another, we must look at the curing mechanisms.

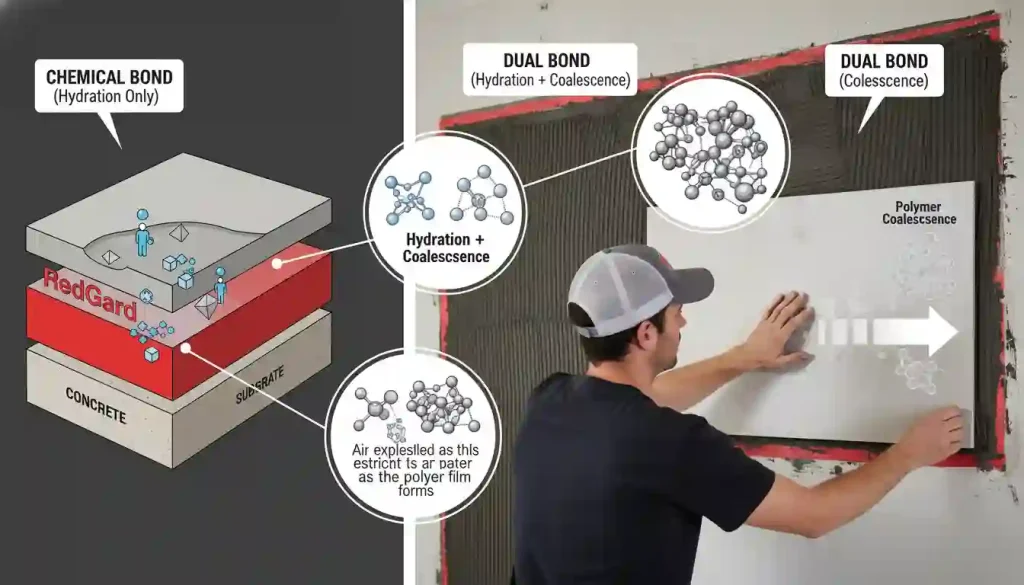

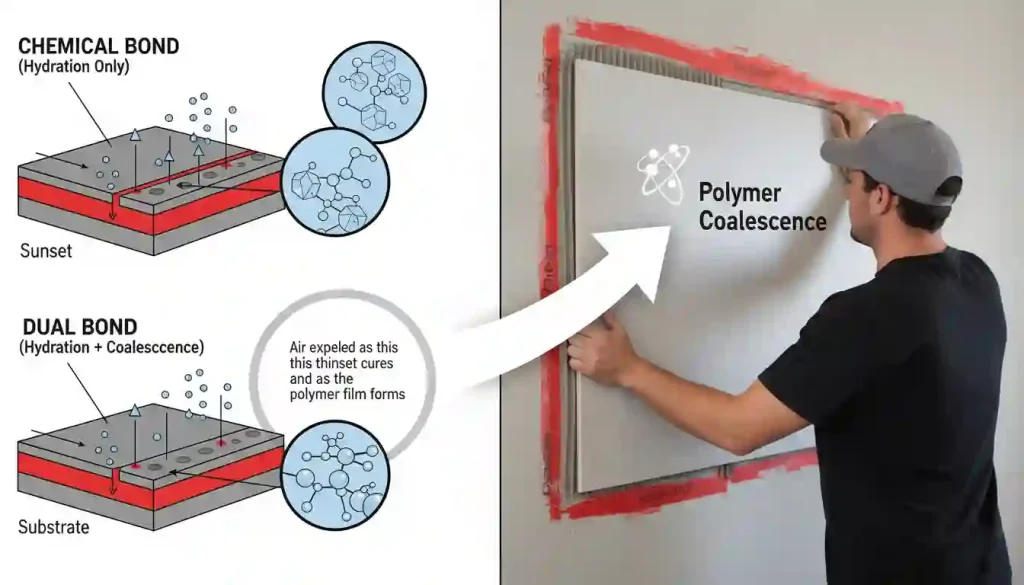

Unmodified thinset cures purely through hydration. When water is added, the Portland cement particles react to form crystalline structures—calcium silicate hydrate (CSH) gel—that interlock and bind the sand particles and the tile together. This is a hydraulic process, meaning it requires the continuous presence of water to complete the reaction and reach full strength. Porous substrates, like unsealed concrete or cement board, can wick moisture away from the thinset, potentially starving the hydration process and weakening the bond.

Modified thinset, on the other hand, has a dual curing mechanism. It cures both through hydration (the cement part) and through coalescence (the polymer part). The latex polymers are microscopic particles suspended in the water. As the water is used up by hydration and evaporates, these polymer particles are forced closer together. Eventually, they fuse into a continuous polymer film throughout the mortar. This film provides the enhanced properties of modified thinset—better adhesion, flexibility, and reduced water absorption.

The critical factor here is that the polymer portion of modified thinset requires air to dry properly. When you sandwich modified thinset between two impervious surfaces—a waterproof membrane like RedGard on one side and a low-porosity tile (like porcelain) on the other—you severely restrict airflow. This can dramatically slow down the drying and curing process. The Tile Council of North America (TCNA) has noted that this “sandwich” effect can extend the full curing time of modified thinset from a standard 28 days to potentially over 60 days.

So, why does the maker of RedGard recommend modified thinset, despite this potential for a prolonged cure? The answer lies in the properties of the membrane itself and the desired performance of the total assembly. RedGard is not just a waterproofing membrane; it’s also an elastomeric crack-isolation membrane, capable of bridging minor in-plane cracks in the substrate. The superior bond strength and flexibility of a modified thinset are crucial for maintaining a tenacious grip on the RedGard surface, especially when subjected to the subtle movements the membrane is designed to handle. The manufacturer has determined that the benefits of this enhanced adhesion outweigh the drawback of a longer curing time.

The Professional’s Approach to Mortar Selection

Beyond the basic “modified vs. unmodified” debate, seasoned professionals consider a broader set of criteria defined by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI). These standards classify mortars based on performance, not just composition.

- ANSI A118.1: The standard for unmodified, dry-set mortars.

- ANSI A118.4: The standard for latex-modified Portland cement mortars.

- ANSI A118.15: A newer, higher-performance standard for “Improved Modified Dry-Set Cement Mortars.”These mortars offer superior bond strength and flexibility and are often required for more demanding installations like large format tiles, glass tile, or exterior applications.

An expert installer knows that for large and heavy tiles (LHT), especially on a wall over RedGard, simply using any modified thinset isn’t enough. They will look for a mortar that not only meets ANSI A118.4 or A118.15 but also has a “T” designation for non-sag properties, preventing heavy tiles from slumping down the wall before the mortar sets. For example, a premium mortar like Custom’s own FlexBond, which is an ANSI A118.4 and A118.15 compliant mortar, is specifically listed as suitable for application over RedGard.

The counter-intuitive insight here is that while unmodified thinset cures chemically better in a sealed environment, a high-quality, polymer-rich modified thinset provides a more tenacious and durable mechanical and chemical bond to the elastomeric surface of the RedGard membrane itself, which is ultimately what prevents delamination and failure in the long term.

Chapter 2: Application Mastery: Beyond the Basics

Proper Application Techniques

The standard procedure for applying thinset over a fully cured RedGard membrane is well-documented. It involves mixing the powdered mortar with water to a peanut-butter-like consistency, allowing it to “slake” (rest) for 5-10 minutes, and then remixing without adding more water. The mortar is then applied to the membrane with the flat side of a trowel to “key it in,” followed by combing with the notched side to create ridges of a uniform height. The tile is then pressed into the mortar with a slight twisting motion to ensure full coverage and collapse the ridges.

Achieving proper thinset coverage is critical. For wet areas, the tile industry standard is a minimum of 95% coverage on the back of the tile. This prevents hollow spots that can collect water and become points of failure.

While this process seems simple, several factors can compromise the installation, including improper mixing, applying too large an area at once (allowing the mortar to “skin over”), or incorrect trowel size for the tile. Interestingly, the journey to a successful tile installation often starts before the tiles are even laid, for instance, in unique construction scenarios like learning to enclose a pole barn to create a conditioned space suitable for tiling.

The Science of Rheology and Adhesion

The “peanut butter consistency” is a practical guideline, but the underlying principle is rheology—the study of the flow of matter. The rheological properties of thinset are crucial. It must be plastic enough to be spread easily but have enough thixotropic behavior (the property of being gel-like when static but fluid when agitated) to hold its shape on the trowel and the wall. The water retention agents in the mix are vital here, preventing the water from evaporating too quickly, which would compromise both hydration and workability.

Adhesion to the RedGard membrane occurs through two primary mechanisms:

- Mechanical Interlocking: The RedGard surface, while smooth, has microscopic pores and texture. The thinset flows into these irregularities, and as it cures, it creates a physical, interlocking connection.

- Chemical Bonding: The cementitious components of the thinset form chemical bonds with the elastomeric surface of the membrane. In modified thinsets, the polymers also form adhesive bonds, significantly enhancing this connection. This is why a high-quality polymer-modified thinset is recommended—it maximizes both mechanical and chemical adhesion to the membrane’s surface.

Understanding these mechanisms also highlights why you should never use pre-mixed “mastics” or adhesives over RedGard in a wet area. These products cure by drying (evaporation) and can re-emulsify when exposed to moisture. Trapped between a waterproof membrane and a tile, they may not cure for weeks and can even chemically damage the membrane. Similarly, one must consider compatibility with other coatings; for example, understanding can you paint over RedGard is critical in areas adjacent to the tiled surface to ensure proper adhesion of all materials.

Directional Troweling and Back-Buttering

A technique that distinguishes the master installer from the novice is directional troweling. When applying thinset, all trowel ridges should be combed in the same direction (typically parallel to the shortest dimension of the tile). When the tile is pressed into the mortar, this allows air to be expelled efficiently from one side, helping to achieve maximum coverage. Random, swirling trowel marks can trap air, creating voids beneath the tile.

Furthermore, for any tile 15 inches or larger on any side (which is common today), back-buttering is non-negotiable. This involves applying a thin, flat coat of thinset to the back of the tile before pressing it into the ridged mortar bed on the wall or floor. This practice is the most effective way to ensure the required 95%+ mortar coverage, especially on large format tiles which often have slight variations in flatness.

An additional expert tip: periodically remove a freshly set tile to check for coverage. Don’t assume your technique is flawless. This simple quality control step can save you from a catastrophic failure down the line. It’s this attention to detail that separates a job that lasts five years from one that lasts a lifetime, much like how understanding the physics of a novel technology like a piezoelectric water heater is key to its proper implementation.

The Hidden Risk of Efflorescence and Water Chemistry

The single most overlooked aspect in the vast majority of online guides and forum discussions is the long-term impact of water chemistry and efflorescence on the thinset behind the tile.

Everyone focuses on preventing water from getting through the tile and grout into the wall cavity, which RedGard does effectively. However, water will inevitably penetrate the grout joints (grout is cementitious and porous, not waterproof). This water will then become trapped between the tile and the RedGard membrane. The thinset layer in this “sandwich” will be intermittently or, in some cases, constantly saturated.

Here’s the problem: All cement-based products, including thinset mortar, contain soluble mineral salts (calcium hydroxide). When water saturates the thinset, it dissolves these salts. As the water slowly evaporates back out through the grout joints, it leaves the salt deposits behind on the grout surface. This is known as efflorescence, the familiar chalky white residue.

While often considered a cosmetic issue, severe and persistent efflorescence points to a more sinister problem. The constant presence of moisture within the thinset layer can lead to a condition where the water becomes highly alkaline. This alkaline solution can, over a very long period, begin to attack the glass content in certain types of tile glazes or even the polymer structure of modified thinsets, potentially leading to a slow degradation of the bond.

Furthermore, if the home has very “hard” water with high mineral content, or if harsh chemical cleaners are used, these chemicals can also become concentrated in the trapped water within the thinset bed. This can create a chemical cocktail that slowly degrades the grout and mortar from the inside out.

The ultimate, rarely-discussed reality is that a tile assembly over a membrane is not a “dry” system behind the tile. It is a “managed water” system. The RedGard ensures this water cannot damage the building structure, but it does not eliminate the water from the system entirely.

The long-term durability of the installation, therefore, depends not just on the initial bond strength, but on the chemical stability of the thinset and grout when subjected to years of saturation with whatever water and chemicals are introduced into the shower.

This is why using a high-quality, dense, polymer-modified thinset and a high-performance grout are not just best practices—they are essential components for ensuring the chemical resilience of the entire system over decades of use.