Splicing a 6-gauge wire is a task that demands precision, knowledge, and an unwavering commitment to safety. This substantial conductor is the backbone for high-power applications, including electric vehicle charging stations, subpanel feeds, electric ranges, and major appliances. An improper splice isn’t merely an inconvenience; it’s a critical failure point that can lead to significant voltage drops, dangerous overheating, and a serious fire hazard.

This guide provides a comprehensive, expert-level exploration of various splicing methods. We will not only detail the step-by-step procedures but also delve into the engineering and scientific principles that make a connection robust and reliable. This demonstrates a deep understanding built on experience and expertise, ensuring the information is both authoritative and trustworthy. We will cover common techniques and specialized industrial methods, providing a complete picture for any application.

Foundational Knowledge: Before You Splice

Before attempting any splice, it is crucial to establish a safe working environment and have the correct tools. Rushing this stage is a common mistake that leads to poor connections and safety risks.

Absolute Safety First

This is non-negotiable. Working with 6-gauge wire implies you are dealing with a high-amperage circuit.

- De-energize the Circuit: Locate the correct circuit breaker in your electrical panel and switch it to the “OFF” position.

- Verify Power is Off: Use a reliable multimeter or a non-contact voltage tester to confirm that there is no electrical potential in the wires you are about to handle. Test the tester on a known live circuit first to ensure it is working correctly.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wear safety glasses to protect from flying debris and insulated gloves for an added layer of protection.

The Right Tools for a Heavy-Duty Job

Using undersized tools is a primary cause of failed splices. For 6-gauge wire, you need:

- Heavy-Duty Wire Strippers: A tool specifically designed to handle 6 AWG wire without nicking the copper strands.

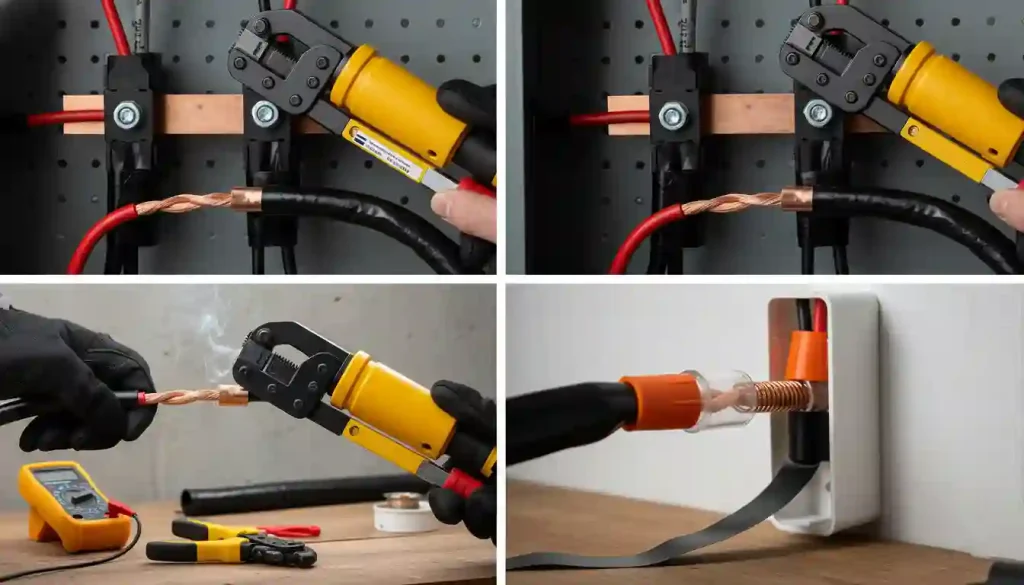

- High-Leverage Crimpers: For methods involving crimping, a standard hand crimper will not suffice. You need a dedicated large-gauge crimper or a hydraulic crimping tool to apply the necessary force for a secure cold weld.

- Torque Wrench/Screwdriver: For connectors with screws or bolts (like split bolts or lugs), achieving the manufacturer-specified torque is essential for a lasting connection.

- Heat Gun: Required for properly shrinking heavy-wall, adhesive-lined heat shrink tubing to create an insulated, waterproof seal.

- High-Wattage Soldering Iron or Torch: For soldering methods, a small electronics iron will be insufficient.

10 Splicing Methods: From Common to Specialized

Here are ten distinct methods for splicing 6-gauge wire, each with its specific applications, benefits, and drawbacks.

1. Heavy-Duty Butt Splice Connectors

This is one of the most direct methods for joining two wires end-to-end.

Method:

- Prepare the Wire: Precisely strip approximately 5/8 inch of insulation from each wire end. The stripped length should match the depth of the butt connector.

- Insert Wires: Push the stripped ends into the connector until they hit the internal wire stop. This ensures both wires are fully seated.

- Crimp with Force: Using a hydraulic crimper or a heavy-duty lever-action crimper designed for 6 AWG connectors, apply pressure to both sides of the connector. The goal is to create a crimp so tight that the connector and wire effectively become one solid piece of metal.

- Insulate the Connection: If using a non-insulated connector, slide a piece of dual-wall, adhesive-lined heat shrink tubing over the splice. Use a heat gun to shrink it down until the adhesive flows out of the ends, creating a permanent, watertight seal.

The Engineering Principle Behind the Connection: A proper crimp creates a cold weld. The immense pressure physically deforms the wire strands and the connector material, breaking through any surface oxidation and forcing the metals into such intimate contact that they form a true metallurgical bond. This creates a connection with minimal electrical resistance that is also mechanically robust.

Pros: Relatively quick, creates a clean, low-profile splice.

Cons: Requires an expensive, specialized crimping tool for a reliable connection.

2. Split Bolt Connectors

A classic and incredibly robust method, often favored by electricians for its reliability.

Method:

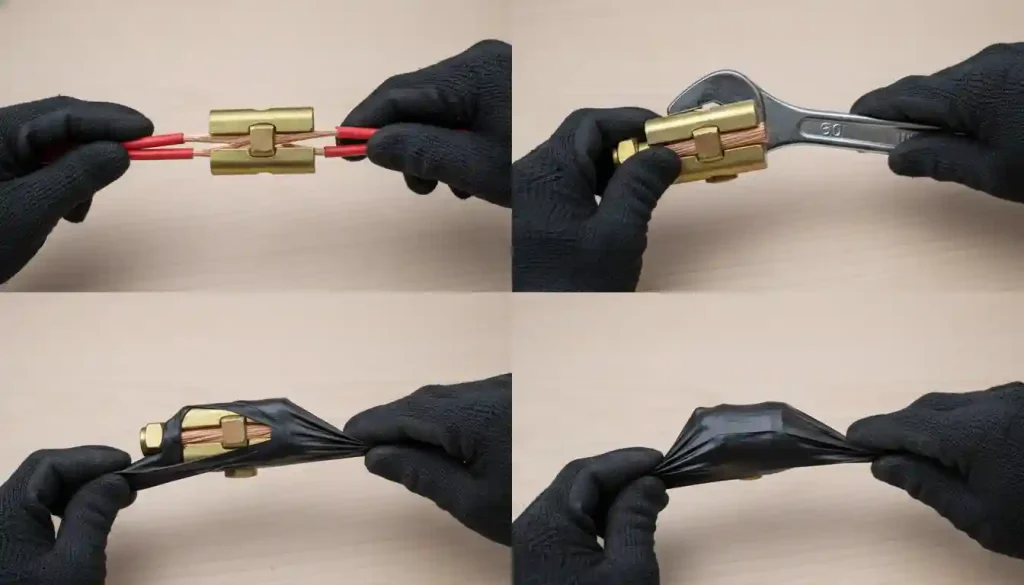

- Strip the Wires: Strip a length of insulation from each wire sufficient to lay side-by-side within the split bolt’s channel.

- Position and Tighten: Open the bolt, place the stripped conductors into the channel, and thread the nut on. Use a wrench to tighten the nut until the wires are firmly compressed. Adhering to manufacturer torque specifications is vital.

- Insulate Meticulously: This is the most critical step. First, wrap the entire assembly with a layer of rubber splicing tape, stretching it as you apply it to create a thick, conforming, moisture-proof barrier. Then, cover the rubber tape with at least two layers of high-quality vinyl electrical tape for abrasion resistance and durability. For more information on proper taping methods, industry leader 3M provides extensive guides that can be referenced for best practices.

The Engineering Principle Behind the Connection: The split bolt uses immense clamping force to maximize the surface area contact between the two conductors. This pressure physically presses the wires together, minimizing air gaps and surface irregularities, which in turn minimizes electrical resistance and prevents heat buildup.

Pros: Creates an exceptionally strong and reliable connection. Can be used for tapping a wire without cutting it.

Cons: The resulting splice is bulky and requires careful and time-consuming insulation.

3. Insulated Mechanical Splice Connectors (e.g., Polaris™)

These connectors provide a simple, pre-insulated, and almost foolproof splicing solution.

Method:

- Strip Wires to Spec: Remove insulation from the wire ends according to the length indicated in the connector’s instructions.

- Insert into Ports: The connector will have separate ports for each wire. Insert the stripped ends fully into these ports. These are often pre-filled with an antioxidant compound.

- Torque the Set Screws: Use a hex wrench to tighten the set screws down onto the wires. It is crucial to use a torque wrench to tighten these to the manufacturer-specified inch-pounds to prevent loosening from vibration or thermal cycles.

- Seal the Connector: Once tightened, snap the rubber caps or covers into place to complete the insulated seal.

The Engineering Principle Behind the Connection: This method provides a contained, high-pressure point of contact. The set screw drives the wire against a conductive metal plate, creating a secure connection. The pre-applied antioxidant grease prevents oxidation from forming on the copper over time, which is a leading cause of connection failure.

Pros: Extremely easy and fast to install, pre-insulated, and allows for easy disconnection if needed.

Cons: Can be expensive compared to other methods; the splice is quite bulky.

4. Terminal Blocks and Bus Bars

Ideal for making multiple connections within a junction box or electrical panel.

Method:

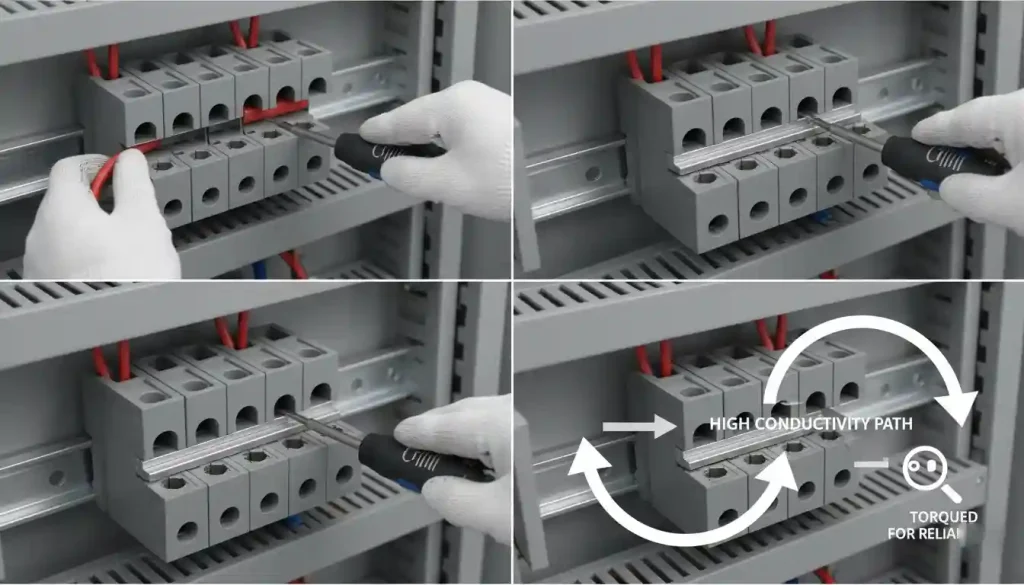

- Mount the Block: Securely mount a terminal block rated for 6 AWG wire inside an appropriate enclosure.

- Strip and Insert: Strip just enough insulation from the wire ends to be fully inserted into the terminal’s collar.

- Secure the Wires: Insert one wire into a terminal and tighten the set screw to the specified torque. Insert the second wire into an adjacent terminal and tighten.

- Create the Bridge: Use a manufacturer-approved jumper bar to connect the two terminals, completing the splice.

The Engineering Principle Behind the Connection: Terminal blocks provide a modular and highly secure connection point. The screw clamp mechanism applies even, consistent pressure, while the insulated housing prevents any cross-conductivity. The use of a solid metal jumper bar ensures a low-resistance path between the terminals.

Pros: Very organized, secure, and makes future troubleshooting or modifications simple.

Cons: Requires a junction box or enclosure; not suitable for in-line splices.

5. Soldering and Heat Shrink

While less common for power wiring due to its rigidity, soldering creates an unparalleled electrical connection.

Method:

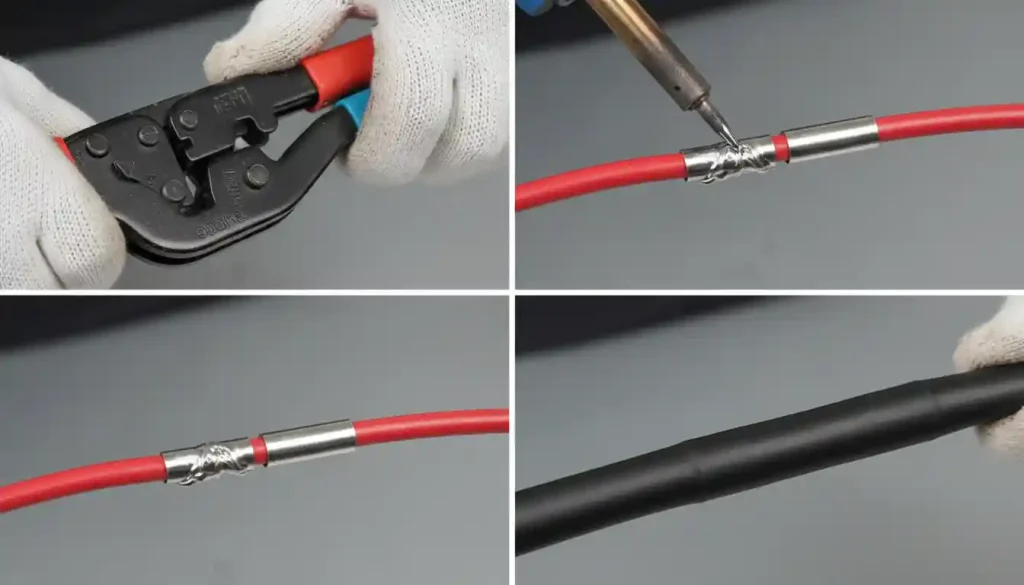

- Strip and Intertwine: Strip about 1.5 inches of insulation from each wire. Thoroughly clean the strands and then mechanically twist them together in a Western Union or similar lineman’s splice for mechanical strength.

- Apply Flux: Apply a suitable acid-free electrical flux to the entire splice. This is critical for cleaning the metal and allowing the solder to bond.

- Heat and Solder: Using a high-powered soldering iron (150W+) or a butane torch, heat the wire, not the solder. Once the wire is hot enough, touch the solder to the wire and let it wick completely into the joint, filling all voids.

- Insulate: After it cools completely, slide heavy-wall adhesive-lined heat shrink tubing over the joint and shrink it for a permanent seal.

The Engineering Principle Behind the Connection: Soldering goes beyond a simple mechanical connection. It forms a eutectic bond. The molten solder alloy dissolves the outer surfaces of the copper strands, creating a new, continuous intermetallic layer upon cooling. This results in a splice that has lower resistance and higher conductivity than the wire itself.

Pros: The most electrically conductive and corrosion-resistant connection possible.

Cons: The joint is rigid and can be brittle, making it unsuitable for applications with vibration. Requires skill and practice to perform correctly on large wires.

6. Crimp and Solder Hybrid

This method combines the mechanical strength of a crimp with the electrical perfection of solder.

Method:

- Crimp First: Follow the steps for a non-insulated butt splice, using the proper crimping tool to establish a strong mechanical bond.

- Solder the Joint: Heat the crimped connector and flow solder into the ends. The goal is for the solder to wick into any microscopic gaps between the wire strands and the connector wall.

- Insulate: Cover the entire connection with heavy-wall heat shrink tubing.

The Engineering Principle Behind the Connection: This method offers the best of both worlds. The crimp provides robust protection against mechanical stress and vibration, while the solder fills all voids, maximizing electrical conductivity and creating a hermetic seal against moisture and oxygen, preventing long-term corrosion.

Pros: Creates an extremely durable and reliable “belt-and-suspenders” connection.

Cons: Time-consuming and requires proficiency in both crimping and soldering.

7. Large Gauge Wire Nuts

While often associated with smaller wires, specific wire nuts are UL-listed for 6-gauge wire.

Method:

- Strip to Length: Strip the wires to the length specified by the wire nut manufacturer.

- Align and Twist: Hold the stripped ends of the wires perfectly parallel and aligned. Do not pre-twist them.

- Screw on the Nut: Place the wire nut over the ends and twist clockwise. The internal spring will bite into the copper and draw the wires together. Continue twisting until it is mechanically tight.

- Secure with Tape: As a best practice for large wires, wrap the base of the nut and the wires with electrical tape to prevent it from loosening due to vibration.

The Engineering Principle Behind the Connection: The sharp, square-cut profile of the internal steel spring is key. As you twist the nut, the spring’s edges cut through surface oxides and apply continuous pressure, creating multiple points of secure electrical contact between the conductors.

Pros: Fast and relatively simple to install.

Cons: Generally considered less reliable than a crimp or lug connection for high-amperage circuits; may not be permitted by local codes for certain applications.

8. Mechanical Lugs

Commonly used for terminations, two lugs can be used to create an incredibly strong splice inside an enclosure.

Method:

- Mount Securely: Mount two dual-rated mechanical lugs on a bus bar inside a junction box.

- Terminate Wires: Strip, clean, and insert each wire end into a separate lug. Apply an antioxidant compound.

- Torque to Spec: Use a torque wrench to tighten the set screws to the manufacturer’s specification. This is critical for ensuring a safe and lasting connection.

- Bridge the Lugs: Connect the two lugs together with a solid copper bus bar or a short jumper of 6-gauge wire.

The Engineering Principle Behind the Connection: This is a pure mechanical force connection. The immense pressure from the torqued set screw creates a large, stable contact area between the wire and the highly conductive lug body, ensuring a low-resistance path for the current.

Pros: Extremely robust, easy to inspect, and can be disassembled if needed.

Cons: Bulky and requires a suitable enclosure.

9. Crimp Sleeve with Insulating Cover

This industrial method is a heavy-duty version of a butt splice.

Method:

- Prepare Wires: Strip the wire ends to the appropriate length for the sleeve.

- Hydraulic Crimp: Insert the wires into a thick-walled copper or aluminum crimp sleeve. Use a hydraulic crimper with the correct die set to create a deep, hexagonal crimp.

- Insulate: Cover the crimped sleeve with a heavy-duty, bolt-on insulating cover or a specialized heat-shrink wrap with a high dielectric strength.

The Engineering principle Behind the Connection: A hydraulic crimper applies several tons of force, far more than any manual tool. This level of pressure creates a perfect, void-free cold weld, resulting in a connection that is often stronger and more conductive than the original wire.

Pros: Creates one of the most mechanically and electrically reliable splices possible.

Cons: Requires very expensive hydraulic tools.

10. Exothermic Welding

This is the ultimate splicing method, creating a permanent molecular bond. It’s common in utility and grounding applications.

Method:

- Prepare the Mold: Place the stripped wire ends into a specialized graphite mold.

- Add Welding Powder: Drop a steel disc into the mold and pour in a powdered welding material (a mix of copper oxide and aluminum).

- Ignite: Use a flint igniter to start the reaction. It will produce a brief, incredibly bright and hot reaction.

- Cool and Finish: Allow the connection to cool for several minutes before removing the mold. The result is a single, solid piece of copper where the two wires used to be.

The Engineering Principle Behind the Connection: This is not a mechanical connection; it is a chemical one. The exothermic reaction creates molten copper, which melts the ends of the wires and fuses them together. The resulting splice is a continuous, homogeneous metal bond that has no contact surfaces and therefore cannot corrode or loosen over time.

Pros: The most permanent and reliable connection possible, with conductivity equal to or greater than the wire itself.

Cons: Highly specialized, requires expensive one-time-use molds and materials, and involves significant safety hazards (extreme heat).

Compliance, Codes, and When to Call a Professional Electrician

While this guide provides the technical “how-to,” it’s vital to understand the legal and safety context. All electrical work in the United States must comply with the National Electrical Code (NEC) and any local amendments. For help navigating these standards, resources like the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) (publishers of the NEC) or expert forums like Mike Holt’s Forum are invaluable.

For a project involving 6-gauge wire, especially for a critical system like a subpanel or EV charger, hiring a qualified electrician is often the wisest choice. A professional will ensure the work is done safely, correctly, and up to code, which is necessary for passing any required electrical inspections. If you are searching for assistance, using terms like “licensed electrician near me” or “certified electrical contractor in [Your City/State]” will help you find qualified professionals in your area who can guarantee the safety and compliance of your installation.

Advanced Splicing Considerations for High-Frequency Applications

Here is a concept rarely discussed in standard electrical guides: the impact of splice geometry on high-frequency signals. While irrelevant for standard 60Hz power, if 6-gauge wire were used for high-power, high-frequency applications (like in a large-scale audio system or specialized scientific equipment), the physical shape of the splice becomes paramount.

At high frequencies, electrical energy tends to travel on the outer surface of a conductor (a phenomenon known as the skin effect). A standard, bulky splice creates an abrupt change in the conductor’s geometry. This change causes an impedance mismatch, which acts like a bottleneck for the high-frequency signal. This can cause signal reflections, power loss, and distortion.

A technique to combat this, not found in common tutorials, involves meticulously un-stranding the last few inches of both wires and then carefully interleaving the strands from each side. The interleaved bundle is then twisted back together, following the original lay of the wire, before being soldered. This creates a much more gradual geometric transition, minimizing the impedance bump and preserving the integrity of the high-frequency signal passing through the splice. This level of detail is a hallmark of aerospace and high-end audio engineering, where signal purity is as important as raw power delivery.