You grab your multimeter to troubleshoot a pesky outlet, and a simple continuity test between the neutral and ground slots produces a tell-tale beep. For a moment, you might feel a sense of relief, thinking the connection is solid. But this seemingly harmless continuity can signal a safe, correctly wired system or a dangerous, hidden electrical hazard waiting to cause problems. Understanding the difference is not just important; it’s critical for the safety of your home and everyone in it.

Many homeowners are surprised to learn that continuity between neutral and ground is actually required and intentional in one specific place: the main electrical service panel. This connection, known as the neutral-to-ground bond, is a cornerstone of modern electrical safety. However, if this continuity exists anywhere else, it points to a serious wiring flaw that can create hazardous conditions, from energized metal surfaces to rendering safety devices useless.

The Core of the Issue: Why Neutral and Ground Are Intentionally Connected

To grasp why your multimeter beeps between neutral and ground, it’s essential to understand the distinct roles these two conductors play. The neutral wire is the primary return path for electrical current under normal operating conditions, completing the circuit back to the power source. The ground wire, on the other hand, is purely a safety feature, designed to carry fault current only when something goes wrong.

The intentional connection between these two wires at the main service panel, and only at the main panel, is mandated by the National Electrical Code (NEC). This single bond ensures that in the event of a ground fault—where a hot wire accidentally touches a conductive surface like a metal appliance casing—there is a low-impedance path for the fault current to flow back to the source. This surge of current is what trips the circuit breaker, instantly cutting power and preventing electric shock or fire.

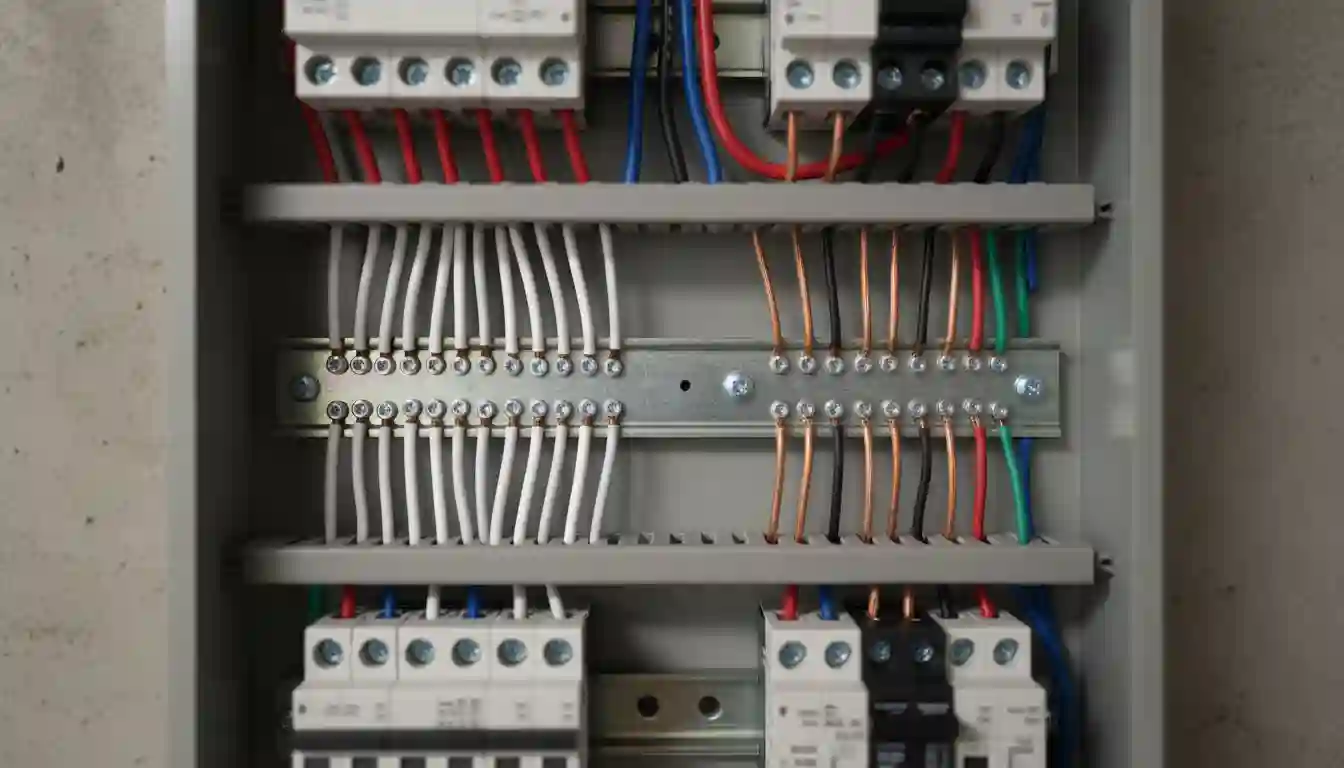

A crucial bond: the neutral and ground bus bars connected in a main electrical panel for safety.

A crucial bond: the neutral and ground bus bars connected in a main electrical panel for safety.What Happens Without the Main Panel Bond?

If the neutral and ground were not bonded at the service panel, the ground wire would lead to a grounding rod, but it wouldn’t have a direct path back to the electrical source (the utility transformer). During a ground fault, the electricity would have no clear, easy route to complete the circuit. This leaves metal appliance frames and other conductive parts energized and extremely dangerous, as the circuit breaker would likely fail to trip.

Without this bond, your electrical system could also be susceptible to voltage instability from external events like lightning strikes. The bond helps to stabilize the system’s voltage with respect to the earth, protecting your sensitive electronics and preventing dangerous voltage spikes.

The Problem: When Continuity Exists Beyond the Main Panel

While the bond at the main panel is a safety requirement, continuity between neutral and ground anywhere else in the electrical system—such as in a subpanel or an outlet—is a significant hazard. This improper connection is often referred to as a “neutral-to-ground fault” or an “improper bond.” It creates parallel paths for the return current to travel, which can have severe consequences.

When neutral and ground are connected downstream from the main panel, the ground wire is no longer just a safety path. It becomes a current-carrying conductor, which it is not designed to be. This means that metal pipes, appliance casings, and other grounded components can become energized during normal operation, creating a constant risk of electric shock.

In a subpanel, neutral and ground bus bars must remain separate to prevent hazardous parallel current paths.

In a subpanel, neutral and ground bus bars must remain separate to prevent hazardous parallel current paths.Identifying the Symptoms of an Improper Bond

Diagnosing an improper neutral-to-ground bond can be tricky, as it often doesn’t present obvious signs until another problem occurs. However, there are several red flags that can point to this dangerous wiring issue:

- Frequent Tripping of GFCI Outlets: Ground Fault Circuit Interrupter (GFCI) outlets work by detecting an imbalance between the hot and neutral currents. An improper bond can cause current to flow on the ground wire, creating the exact imbalance that GFCIs are designed to detect, leading to nuisance tripping.

- Flickering Lights or Voltage Fluctuations: When the ground wire carries current, it can interfere with the stable flow of electricity, sometimes causing lights to flicker or appliances to behave erratically. If you notice persistent flickering, it’s a sign that warrants investigation.

- Audible Buzzing or Humming: Strange noises coming from outlets, switches, or the electrical panel can indicate loose connections or improper current flow, both of which can be related to faulty neutral-ground bonding.

- Receiving a Mild Shock: One of the most direct and dangerous signs is receiving a slight tingling or shock from touching metal appliances, faucets, or switch plates. This indicates that conductive surfaces have become energized due to current flowing on the ground path.

Sometimes, troubleshooting complex issues can feel overwhelming. For instance, diagnosing a furnace problem like a Trane XV80’s flashing red light requires a systematic approach, much like tracing an electrical fault. Both situations highlight the importance of understanding the system’s fundamentals before jumping to conclusions.

Solution: How to Test and Verify Proper Continuity

Testing for continuity between neutral and ground is a straightforward process, but it requires caution and a clear understanding of what the results mean. The primary tool for this job is a multimeter set to the continuity or resistance (Ohms) setting.

Step-by-Step Testing Procedure

Safety First: Before performing any test on an electrical circuit, always turn off the power to that circuit at the main breaker panel. Use a non-contact voltage tester to confirm that the power is off before proceeding.

- Set Your Multimeter: Turn the dial on your digital multimeter to the continuity setting, which is often indicated by a symbol that looks like sound waves. When you touch the probes together, the meter should beep, indicating a complete circuit.

- Test at an Outlet: With the power off, insert one probe into the neutral slot (the larger of the two vertical slots) and the other probe into the ground slot (the semi-circular hole).

- Interpret the Results: In a correctly wired system, the multimeter should beep, indicating continuity. This is because both the neutral and ground wires trace back to the same bonded point in the main service panel.

- Test at a Subpanel (If Applicable): If you are testing at a subpanel, the rules are different. Here, the neutral and ground bus bars must be kept separate. Turn off the main breaker feeding the subpanel. Place one probe on the neutral bus bar and the other on the ground bus bar. The meter should not beep. If it does, there is an improper bond in the subpanel that must be corrected.

Understanding the nuances of electrical work is similar to home improvement projects where details matter, such as deciding between a skim coat vs. primer before painting. In both cases, knowing the correct application prevents future problems.

Troubleshooting an Improper Bond

If you detect continuity where it shouldn’t be (like in a subpanel) or suspect an issue due to symptoms like tripping GFCIs, the problem is likely a miswired connection. Common culprits include a bonding screw or strap incorrectly installed in a subpanel, or a neutral and ground wire mistakenly connected together in an outlet or junction box. Pinpointing the exact location requires a methodical approach, often best left to a qualified electrician who can safely trace the circuit and correct the wiring.

Understanding the “Why”: A Deeper Dive into Electrical Safety

The concept of a single, primary bonding point is central to the safety of the entire electrical system. This design ensures a clear and predictable path for fault currents, allowing overcurrent protection devices like circuit breakers and fuses to function as intended. When multiple bonds exist, the system becomes unpredictable and dangerous.

The Dangers of Parallel Paths

Think of electricity like water; it will always take all available paths back to its source. When you improperly bond neutral and ground in a subpanel, you create a parallel path for the neutral current to flow on the ground wire. This division of current means that the grounding system—including the metal frames of your appliances and the green wire in your cords—is now carrying a portion of the normal operating current.

This situation is especially dangerous if the neutral wire were to become loose or broken. In that scenario, the ground wire would become the primary return path, potentially carrying the full load current. Ground wires are typically smaller than neutral conductors and are not designed for continuous current, which could cause them to overheat and create a fire hazard. Even more alarming, a broken neutral could energize every grounded surface in your home at 120 volts, a life-threatening situation.

Just as a small wiring error can compromise an entire electrical system, other home issues like paint peeling off walls like rubber can indicate a deeper underlying problem that needs to be addressed correctly at the source.

Key Differences Summarized

To ensure clarity, here is a table that breaks down the essential differences in how continuity between neutral and ground should be treated in different parts of your electrical system.

| Location | Expected Continuity Result | Reasoning | Potential Hazard if Incorrect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Service Panel | Yes (Continuity Expected) | The neutral and ground bus bars are intentionally bonded here by code to provide a safe path for fault current. | No bond can prevent breakers from tripping during a fault, leading to shock and fire risks. |

| Subpanel | No (No Continuity) | Neutrals and grounds must be isolated (floating) to prevent the ground wire from becoming a current-carrying conductor. | Bonding here creates parallel paths, energizing grounded surfaces and creating a shock hazard. |

| Outlets/Receptacles | Yes (Continuity Expected) | A properly wired outlet will show continuity because both paths lead back to the bonded main panel. | Lack of continuity could indicate a broken ground wire, leaving the outlet unprotected. |

| Appliances (Unplugged) | No (No Continuity) | There should be no connection between the neutral and ground prongs of an appliance’s plug itself. | Continuity could indicate an internal fault in the appliance, making it a shock risk when plugged in. |

Beyond the Panel: Grounding and Bonding for Separately Derived Systems

The principle of a single, inviolable neutral-to-ground bond at the main service entrance is the foundation of electrical safety. This point ensures that fault current has a reliable, low-impedance path to trip a breaker. But what happens when the main service is no longer the source of power? During a power outage, the introduction of a backup generator or an inverter system creates what is known as a “separately derived system,” and the rules of bonding become critically important in a new way.

A separately derived system is an electrical power source that has no direct connection to the primary source’s circuit conductors. When you connect a generator to your home using a proper transfer switch, the switch physically disconnects your home’s wiring from the utility lines. At that moment, your home’s electrical system, now powered by the generator, is electrically isolated from the utility’s transformer and, crucially, from the main panel’s neutral-to-ground bond. Without further intervention, the entire safety grounding system in your home would become ineffective. A short circuit from a hot wire to an appliance’s metal frame would energize it, but the fault current would have no path back to the generator to trip the generator’s breaker, creating a severe shock hazard.

To solve this, a new neutral-to-ground bond must be established for the new power source. This ensures the safety ground remains effective during backup power operation. This is where a deep understanding of generator types becomes essential. Portable generators are typically sold in one of two configurations:

- Bonded Neutral Generators: In these units, the generator’s neutral conductor is electrically bonded to the frame of the generator, which is connected to the ground pin on its outlets. This type of generator is safe for standalone use, such as at a campsite or a construction site where it is the sole source of power. It creates its own reference to ground, and any fault in a connected tool will have a path back to the generator, tripping its breaker.

- Floating Neutral Generators: In these models, the neutral and ground conductors are kept separate, or “floating.” These are designed for situations where the generator will be connected to a pre-existing, bonded electrical system, such as a home with a transfer switch. The assumption is that the system it connects to will provide the necessary neutral-to-ground bond.

The danger arises from a mismatch between the generator type and the home’s connection method. The National Electrical Code requires careful consideration of this relationship. If a “bonded neutral” generator is connected to a house through a standard transfer switch that only switches the hot legs and leaves the neutral connected back to the main panel, a hazardous situation is created. The system now has two neutral-to-ground bonds—one in the main panel and one at the generator. This creates the very parallel paths for current on the grounding wires that must be avoided, potentially energizing conductive surfaces and tripping GFCI devices.

Conversely, using a “floating neutral” generator with a transfer switch that does switch the neutral wire away from the main panel is equally dangerous. In this scenario, the system has no neutral-to-ground bond at all while on generator power.

The correct and safe solution depends on the transfer switch installation. Systems using a transfer switch that does not switch the neutral conductor require a floating neutral generator; the bond at the main service panel remains the single point of bonding for the system. For systems where the transfer switch disconnects the service neutral, a bonded neutral generator (or a floating neutral generator that has a bond added) is required to re-establish a ground reference. Some homeowners create a “bonding plug”—a simple male plug with a jumper connecting the neutral and ground prongs—to safely convert a floating neutral generator to a bonded one for standalone use, and then remove it when connecting to their home’s system.

Ultimately, the core safety principle remains unchanged: a single, effective neutral-to-ground bond must always exist for the active power source. When that source changes from the utility to a generator, the location of that bond must be intelligently managed. This often overlooked detail is a critical component of ensuring that a backup power system provides not just convenience, but uncompromising safety.

Final Thoughts on Ensuring Electrical Safety

The beep of a multimeter testing for continuity between neutral and ground can be reassuring or alarming—it all depends on where you are testing. In your main electrical panel and at your outlets, that continuity is a sign of a properly grounded system designed to protect you. Anywhere else, particularly in a subpanel, it signals a dangerous wiring error that demands immediate attention.

Never underestimate the importance of proper grounding and bonding. It is the foundation of electrical safety in your home. If you are ever in doubt about your home’s wiring, or if you experience any of the warning signs of an improper bond, do not hesitate to contact a licensed electrician. A professional can quickly and safely diagnose the issue, ensuring that your electrical system is not a hidden danger but a reliable and secure source of power.